Welcome Everyone! Happy One Health Day 2024!

November 3, 2024, is a good day for me to begin my monthly blog! In this blog, I'm going to share with you my thoughts on how a One Health-based approach could be incorporated into primary care. My focus will be on the U.S. since its primary care needs improvement. But these principles could be applied to any country. The One Health example that I will discuss will be microbiome health.

Moving From Organ-Based to One Health-Based Primary Care

The highly specialized, organ-based systems approach to medicine has provided an in-depth understanding of disease processes, but it has siloed and fragmented healthcare, particularly in the U.S. This reliance upon specialized care has produced inadequate and expensive outcomes in the U.S. which spends more on healthcare, but has the lowest life expectancy, than any other large, wealthy country[1].

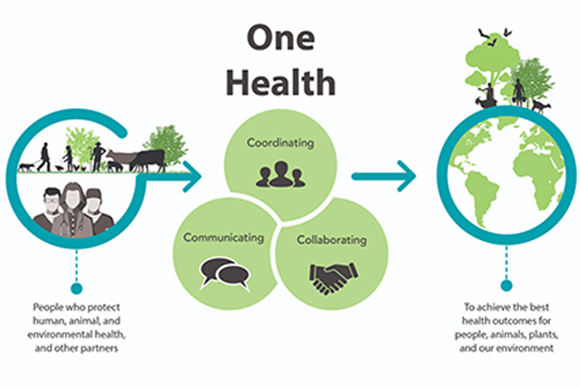

One Health is the concept that human, animal, plant, environmental, and ecosystem health are linked. This concept provides a framework for identifying and addressing the root causes of complex health challenges[2].

The One Health concept can be represented as a multi-dimensional matrix that would serve as the foundation for innovative primary care. The first part of the matrix recognizes the linkages between human, animal, plant, environmental, and ecosystem health. The second part addresses health at the microbial/cellular, individual, and population levels. Psycho-social and economic factors constitute the third part of the matrix since they are major determinants of health[2,3].

Organ-Based Primary Care and Its Limitations

The current primary care model divides the body into organ systems to track their status using physiological measurements and imaging studies looking for anomalies such as irregular heart rate and rhythm, blood pressure deviations, metabolic chemistry and blood count abnormalities, breast cancer screening (i.e., mammograms), and colon cancer screening (i.e., colonoscopies). While useful and important, this approach is more reactive than proactive in preventing disease and promoting health.

The U.S. healthcare system is built for specialty, not primary, care. There are many reasons for this including financial incentives and medical education that are specialty focused[4]. Fewer medical students are choosing careers in primary care[5].

The American Association of Medical Colleges projects that by 2034, the US will have a shortage of between 17,800 and 48,000 primary care physicians. Increasing retirements and burnout have reduced the numbers of practicing primary care physicians. The COVID-19 pandemic hastened the exodus of many healthcare providers.[6]

One Health-Based Primary Care Example: Microbiome Health

We live in a microbial world. Our bodies are mostly microbial. The Human Microbiome Project has revealed that bacterial cells outnumber human cells in our bodies[7]. Evidence suggests that our microbiome is as important for our health and well-being as any organ. Our bodies function through intercellular signaling. Microbes talk to microbes. Microbes talk to cells. Cells talk to cells and microbes[8].

While we typically rely on sounds to communicate, microbes and cells communicate through chemicals[9][10]. Microbes are also sharing antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) at rates faster than we can develop new antimicrobials, and the gut microbiome might be serving as a reservoir of ARGs[11].

The gut has varying concentrations of microbes culminating in the colon where primarily anaerobic bacterial communities up to 100 billion cells per gram reside for several days before being expelled. The composition of the gut microbiota varies, but Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia represent the major phyla[12].

Illness can occur when the microbiome becomes imbalanced, a condition known as dysbiosis, or when pathogens invade. Dysbiosis appears to increase noncommunicable disease risk such as autoimmune diseases like asthma, neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson's disease, and inflammatory bowel disease such as Crohn's disease in susceptible individuals and might contribute to disease progression. Understanding the genesis and impacts of dysbiosis should be a research priority in primary care. Antibiotics, lifestyle, genetics, other drugs, and hygiene might be contributing factors as well as diet, food additives, and food preservatives[13].

Bacteriophages have received renewed interest in recent years not only as potential therapies to treat dysbiosis but also as antimicrobial adjuncts or substitutes[14]. Lytic phages have great potential to address antimicrobial resistant infections, but much work remains to take full advantage of their potential. The technology to isolate them from environmental samples has not advanced much since the early 20th century. In March 2016, the first successful use of intravenous bacteriophage therapy occurred against a multi-antibiotic-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infection at UC San Diego. UC San Diego subsequently established the first, and only, Center for Innovative Phage Applications and Therapeutics in the U.S[15].

Technological advances have revolutionized microbiome analysis, and previously unculturable microbes can now be identified. Artificial intelligence and machine learning have also been applied to microbiome research and may inform strategies for improving primary care[16][17].

Interest in microbiome health is exploding, and the demand for probiotics alone is estimated to grow at a CAGR* 13.2% from 2023 to 2030. In 2022, the U.S. probiotics market was valued at $27.47 billion[18]. Americans purchase these products over the counter, often without medical advice or supervision because many physicians have only a general knowledge about them and about the microbiome[19].

This gap in care represents an opportunity for addressing unmet needs. Medical education and training need to be updated. Penn State University has established a One Health Microbiome Center, but it is not targeted for patient care[20].

Teaching One Health-Based Primary Care in Medical Schools

A survey of U.S. medical schools found that only 56 percent have included One Health-related subject matter into their curriculum. The authors found that there is a lack of One Health expertise and that curricula are already packed with other material[21]. Some medical schools, such as UCLA, are creating new fields, such as "Evolutionary Medicine" that combines ecology, evolutionary biology, anthropology, psychology, and zoology to better understand disease[22].

The purpose of One Health is to bridge gaps and facilitate broad, systems-based thinking. Medical schools are showing interest which is important. Educating and training the next generation of practitioners who can provide One Health-based primary care, such as microbiome health, should be a national priority.

References

- Kaiser Family Foundation. "The U.S. Has the Lowest Life Expectancy Among Large, Wealthy Countries While Far Outspending Them on Health Care." December 9, 2022. Link

- Kahn LH. (2021) "Developing a one health approach by using a multi-dimensional matrix." One Health. 13: 100289. Link

- Hudon C, Dumont-Samson O, Breton M, et al. (2022) "How to Better Integrate Social Determinants of Health into Primary Healthcare: Various Stakeholders' Perspectives." International Journal Environmental Research and Public Health. 19(23): 15495. Link

- Fong, K. "The U.S. Health Care System Isn't Built for Primary Care." Harvard Business Review. September 28, 2021. Link

- Knight V. "American Medical Students Less Likely To Become Primary Care Doctors." KFF Health News. July 3, 2019. Link

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). "The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2019 to 2034." June 2021. Link

- NIH Human Microbiome Project. Link

- Combarnous Y and Nguyen TMD. (2020) "Cell Communications among Microorganisms, Plants, and Animals: Origin, Evolution, and Interplays." International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21(21): 8052. Link

- Krautkramer KA, Rey FE, Denu JM. (2017) "Chemical signaling between gut microbiota and host chromatin: What is your gut really saying?" Journal of Biological Chemistry. 292(21): P8582-8593. Link

- Liu H, Wang J, He T, et al. (2018) "Butyrate: A Double-Edged Sword for Health?" Advances in Nutrition. 9(1): 21-29. Link

- Crits-Christoph A, Hallowell HA, Koutouvalis K, et al. (2022) "Good microbes, bad genes? The dissemination of antimicrobial resistance in the human microbiome." Gut Microbes. 14(1): 2055944. Link

- deVos WM, Tilg H, Van Hul M, et al. (2022) "Gut microbiome and health: mechanistic insights." Gut. (71): 1020-1032. Link

- Hrncir T. (2022) "Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis: Triggers, Consequences, Diagnosis and Therapeutic Options." Microorganisms. 10(3): 578. Link

- Hitchcock NM, Nunes DDG, Shiach J, et al. (2023) "Current Clinical Landscape and Global Potential of Bacteriophage Therapy." Viruses. 15: 1020. Link

- UC San Diego School of Medicine. "Center for Innovative Phage Applications and Therapeutics." Link

- Young RB, Marcelino VR, Chonwerawong M, et al. (2021) "Key Technologies for Progressing Discovery of Microbiome-Based Medicines." Frontiers in Microbiology. 12: 685935. Link

- Medina RH, Kutuzova S, Nielsen KN, et al. (2022) "Machine learning and deep learning applications in microbiome research." 2:98. Link

- Grand View Research. "Probiotics Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report." Link

- Fijan S, Frauwallner A, Varga L, et al. (2019) "Health Professionals' Knowledge of Probiotics: An International Survey." International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 16(17): 3128. Link

- Penn State Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences. "One Health Microbiome Center Mission." Link

- Docherty L and Foley PL. (2021) "Survey of One Health programs in U.S. medical schools and development of a novel One Health elective for medical students." One Health. 12: 100231. Link

- UCLA School of Medicine. "Evolutionary Medicine Program." Link